Asking big companies to be nice to workers is framed in a positive light, but trying to back it up with any more serious action gets you called out as “curt,” “angry” and “unbending.”

By Julie Hollar and Kat Sewon Oh, FAIR.org

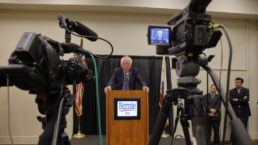

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) is the new chair of the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions—and the New York Times has something to say about it. In a piece by veteran reporter Sheryl Gay Stolberg (2/12/23) headlined, “Bernie Sanders Has a New Role. It Could Be His Final Act in Washington,” the paper demonstrates once again (FAIR.org, 2/24/16, 10/1/19, 1/30/20) how the lens through which corporate media view progressive politicians colors their coverage.

Stolberg kicks things off by noting that Sanders has “made no secret of his disdain for billionaires,” and now “has the power to summon them to testify before Congress—and he has a few corporate executives in his sight.” On the list: Amazon founder (and owner of the Washington Post) Jeff Bezos and Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz. Writes Stolberg:

He views them as union busters whose companies have resorted to “really vicious and illegal” tactics to keep workers from organizing. He has already demanded that Mr. Schultz testify at a hearing in March.

We might point out here that these “views” aren’t just Sanders’ opinion. Less than two weeks before Stolberg’s piece appeared, a judge ruled that Amazon violated labor law trying to stop unionization efforts in Staten Island warehouses. (Stolberg might also see her colleague David Streitfeld’s lengthy investigation published in the Times—3/16/21—headlined, “How Amazon Crushes Unions.”) The National Labor Relations Board had filed 19 formal complaints against Starbucks as of last August—as Stolberg herself acknowledges two-thirds of the way into the article—and just ruled against the company in a union-busting case in Philly.

‘Angry letter’

But another passage caught our eye:

Mr. Sanders is clearly operating on two tracks. Last week, in a move that might surprise critics who view him as unbending, he partnered with a Republican, Senator Mike Braun of Indiana, to call on rail companies to offer seven days of paid sick leave to their workers—a provision that the Senate defeated last year when it passed legislation to avert a rail strike.

But he also sent a curt letter to Mr. Schultz, giving him until Tuesday to respond confirming his attendance at the hearing. That followed an earlier, angry letter in which Mr. Sanders urged the Starbucks chief to “immediately halt your aggressive and illegal union-busting campaign.” A Starbucks spokesman said the company was considering the request for Mr. Schultz to testify and was working to “offer clarifying information” about its labor practices.

To the Times, this is a lesson in contrasts in which Sanders can sometimes be flexible and pragmatic, but at others “unbending” and “angry.” But the truth is that the “two tracks” here are actually following exactly the same script: calling on corporate bosses to treat their workers fairly, and if they don’t, asking them to come in for questioning.

Sanders issued his warning to Schultz last March when Schultz took over as interim CEO, writing, “Please respect the Constitution of the United States and do not illegally hamper the efforts of your employees to unionize.” Nearly a year later, with no progress, he’s calling Schultz in to testify.

In the case of the rail companies, local news station WAVY (2/11/23) reported that “Sanders promises if he doesn’t see change, he will question railway executives under oath in a Senate hearing.” Sound familiar?

The only difference between the two—and what really matters to the Times—is that in one case, a Republican joined him, which by corporate media’s definition makes it a flexible and pragmatic action, whereas in the other, no Republicans on the committee signed the letter. No bipartisanship? No pragmatism. It’s a golden rule for political reporters that encourages compromise for the sake of compromise, no matter what the public actually wants.

And it elevates empty rhetoric over more serious action. Asking big companies to be nice to workers is framed in a positive light, but trying to back it up with any more serious action gets you called out as “curt,” “angry” and “unbending.”

(We’ll let you decide for yourself if this standard-looking letter from the committee, giving Schultz a week to respond and a month to prepare testimony, is “curt.” It’s not clear what Stolberg was looking for to make it more polite; apologies for taking up a very important man’s time?)

The number of negative words used to describe Sanders in this one article is remarkable. In addition to “unbending,” “curt” and “angry,” he’s “combative,” full of “disdain,” a former “left-wing socialist curiosity” who “rants,” makes demands, has a “trademark scowl” and can almost never be seen smiling in the Capitol.

‘Ever combative’

Bernie Sanders “already has,” Stolberg writes, “provide[d] a wonderful target for Republicans to shoot at.”The end of the piece perfectly illustrates the eternal disconnect between Sanders and reporters like Stolberg:

With the recent retirement of Senator Patrick J. Leahy, a Democrat who served for 48 years, Mr. Sanders is finally the senior senator from Vermont. Asked how he felt, he said, “Pretty good.” Then, ever combative, he shot back, “How do you feel?”

“How do you feel?” Them’s fightin’ words!

Stolberg continued:

He said people who wonder about whether he will run again—and by people, he meant reporters—should “keep wondering.”

Why? “Because I’ve just told you, and this is very serious,” he said, wearing his trademark scowl. “If you think about my record, I take this job seriously. The purpose of elections is to elect people to do work, not to keep talking about elections.”

Just as they prioritize compromise over meaningful political action, political reporters consistently prioritize the horserace over substantive issues, all to the detriment of democracy. But those reporters cling to the fiction that they’re strictly observers—and anyone who tries to suggest otherwise is dismissed under a steady stream of pejorative adjectives.

Recent Posts

What To Do When You See ICE In Your Neighborhood

July 14, 2025

Take Action Now How can you deter the Trump administration’s immigrant deportation machine when it pops up in your community? Follow these…

ICE Campaign Of Violence Will Lead To More Deaths

July 14, 2025

Take Action Now Jaime Alanis’s death shows the horrific consequences of a secret police force behaving with utter impunity.By Natasha Lennard, The…

Hague Group: “Concrete Measures” or Sack of Cement? Will It Move to Sanctions, Peace Force and Ensuring Aid to Gaza?

July 13, 2025

Take Action Now Will the meeting in Colombia be a coalescence of global opinion driving states to just action — or just more rhetoric from various…

Why Are Democratic Lawmakers Still Meeting With Netanyahu?

July 12, 2025

Take Action Now Pictures show Democrats like Chuck Schumer standing next to Netanyahu, smiling.By Sharon Zhang, Truthout A bipartisan group of…