The fear of most Black parents is now shrouded in a double threat of potential harm.

By Alexandra Jane, The Root

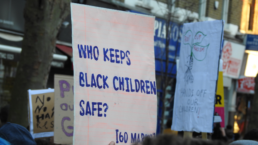

Every time there is news of a mass shooting in this country, we go through the same cycle. In the beginning, there is outrage, and by the end, nothing seems to have changed but the number of hashtags on our social feeds in honor of the dead. In the middle of this worn and tired cycle are conversations about new laws, and new public safety measures. Most of which revolve around gun control, and policing. In the wake of the most recent school shooting in Uvalde, TX, The Washington Post reports that republican lawmakers are being called upon to place more police and armed security in schools. While some white parents are fearful of the idea of more guns entering school buildings, Black parents are having to reckon with the possibility of there not only being more deadly weapons around their children, but more police as well. For a community whose relationship with law enforcement is already so fraught, parents of Black and Latin X children are more terrified than ever.

Shane Paul Neil, a 44-year-old father of two thought of his own children as most parents did, in the days following the massacre of 19 children at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde. As he grappled with the possibility of a double threat in his children’s schools — increased chances of random gun violence, as well as racial profiling by police — he voiced his fears online in a tweet that has now gone viral. “As a black father I now have two potential threats to be concerned over.”

“For White parents it was, ‘we don’t want to bring more guns into school,’” he told The Washington Post. “For myself and other Black parents, it’s that we don’t want to force police interaction in school with our children in particular.”

Statistics show that Black and Latin X students are suspended and expelled at significantly higher rates than their white peers. They are also most likely to be arrested both in and outside of the classroom, at times leaving them with a record that stays with them into their adulthood. “It only takes one incident for my son or daughter to have an arrest record, a juvenile record,” Neil says, “and those things stick with you, they follow you.”

Recent Posts

Israel and American Hawks are Pushing U.S. to Iran War With Catastrophic Consequences

February 23, 2026

Take Action Now At the World Health Assembly in May, member states may endorse an unprecedented strategy declaring that health is not a cost – but…

A Child’s View of the Attack on Venezuela. And a Peace Flotilla

February 23, 2026

Take Action Now At the World Health Assembly in May, member states may endorse an unprecedented strategy declaring that health is not a cost – but…

How to Organize Safely in the Age of Surveillance

February 22, 2026

Take Action Now From threat modeling to encrypted collaboration apps, we’ve collected experts’ tips and tools for safely and effectively building a…

‘The Siege Must Be Broken’: Countries Called to Ship Fuel to Cuba After Trump Tariffs Struck Down

February 21, 2026

Take Action Now The US Supreme Court’s ruling “implies that Trump’s recent order imposing tariffs on countries selling oil to Cuba exceeds the…