Exposing the flawed logic of a centrist pivot for Democrats

By Sam Rosenthal

Nearly exactly a year later, two narratives have taken hold about the electoral wipeout Democrats experienced in 2024. The first is the Democratic Party, weighed down by an unpopular and enfeebled presumptive nominee who had overseen unpopular foreign wars and economic carnage at home, failed to articulate a vision other than “ we’re not Trump”. The second is that Democrats, after routing Donald Trump in 2020, moved too far to the left, losing the coveted “moderate” vote and the entire election.

Progressives have stuck mostly to the first narrative. As political director at RootsAction, I was among the first group of detractors encouraging Joe Biden not to seek a second term as president. Our “Don’t Run Joe” campaign, launched after the 2022 midterm elections, was derided by party insiders and the corporate media. At the time, we saw Biden as politically vulnerable and personally unpersuasive; this view was only intensified after October 7, 2023, when Biden became a full-throated backer of Israel’s genocide in Gaza. Where we saw Biden and his administration hemorrhaging support across multiple demographics, party insiders painted a far sunnier picture. That our view was ultimately vindicated by the Democrats’ failures in 2024 is cold comfort.

The moderate wing of the Democratic Party, however, has come away from the 2024 bloodbath with substantially different lessons. In their reading, the error of 2024 was not that Biden ignored the progressive flank of the party; rather, it was that he was too supportive of it. Moving forward, these pundits argue, Democrats should pivot back to the center to capture a larger proportion of voters and thereby seal future electoral victories. The latest addendum to this line of thinking is the splashy Deciding to Win report, a project by Welcome, a corporatist, centrist think tank. While the report has garnered a great deal of coverage, and online adherents, a closer look reveals a void, words without signification, and another excuse to heap blame on progressives without any data to undergird their claims.

Who Are the Corporatists Running Welcome?

Everything you need to know about the Deciding to Win report can be gleaned by clocking its provenance. Welcome, and its PAC, the Welcome PAC, are largely funded by donors who are firmly ensconced in the superstratum of the ultra-wealthy. Big funders include David and Patricia Nierenberg—David was a national finance chair on Mitt Romney’s 2012 campaign—and Michael Eisenson, a managing director of a private equity firm.

Welcome trumpets its electoral victories and ardent support for “pragmatic” candidates, that favorite designation of the moderate persuasion, but their electoral record is breathtakingly poor. In the last cycle, Welcome PAC made independent expenditures in nine congressional races; only one of its supported candidates, incumbent Marie Gluesenkamp-Perez, won. A win rate of roughly 11 percent is not exactly a strong leg to stand on when making pronouncements about how the Democratic Party should be reorganized. For all its bluster about charting a new course for the party, Welcome PAC’s spending on behalf of candidates seems to largely follow longstanding patterns that have been criticized for enriching consultants while doing little to engender real support for its candidates: slick ad buys and astroturf campaigns. Deciding to Win even takes an aside to fire shots at canvassing and phone banking, the bread and butter of grassroots campaigning. In short, this does not appear to be an organization particularly curious about anything other than business as usual.

A Guide to Popularity

Deciding to Win’s central thesis is that, in 2024, Democrats adopted unpopular positions, mostly forced on them by the party’s progressive wing, and that those positions doomed them with the broader electorate. To support this argument, they point to “moderate” candidates who overperformed 2024 trends while running on more “popular” platforms. The authors devote a great deal of time to enumerating which positions are popular and which are not.

Some of these arguments are laughably flimsy. In one section, the authors report, gravely, that certain Democratic positions are so devastatingly unpopular that they should be abandoned at once. These include proposals to “abolish the police,” “abolish prisons,” and “provide free healthcare to undocumented immigrants.” That the current Democratic Party—or any in the past—has advocated for the abolition of prisons or police is laughable.

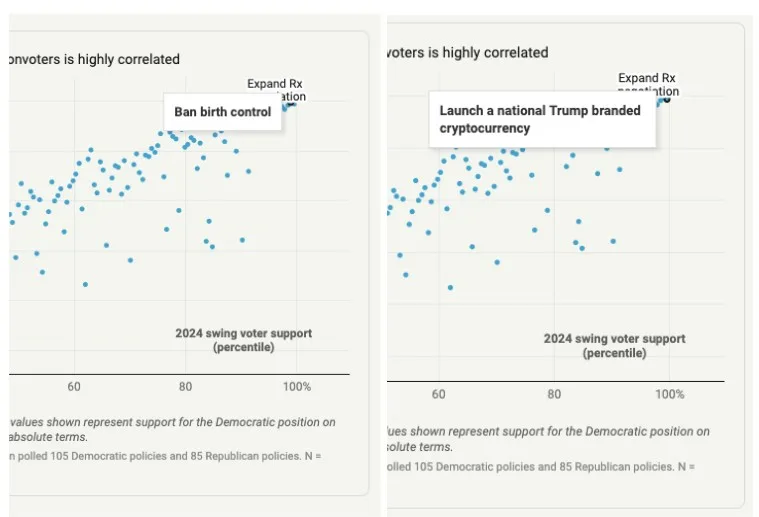

These straw man slugfests are punctuated by some neat sections of statistical cherry-picking. In the fourth section, for example, the authors present a tidy graph of policy support among swing and nonvoters. It ostensibly shows that both groups are aligned on which policies they support, meaning Democrats could capture them by running on “popular” policies while eschewing the unpopular ones.

To underline this, they highlight two data points: “increase refugee admissions,” which polls around eight percent, and “expand prescription drug price negotiation,” which polls above ninety-five percent. The logical extension is that Democrats should ignore policies pushed by progressives—like comprehensive immigration reform—and instead stick to those preferred by moderates.

But the problem with this analysis is that there isn’t a coherent trend among the hundred-plus policies the report polled. Some policies with similarly low support include “increase police funding” and “end all government benefits for undocumented immigrants.” Meanwhile, expanding Medicare coverage polls above ninety percent, a policy that, elsewhere in the report, the authors imply is unpopular and untenable. (Perplexingly, the survey also records near-universal approval for “ban birth control” and “launch a national Trump-branded cryptocurrency.” Surely the authors don’t think Democrats should run on those planks.)

All that this scale of popularity for more-than-100 policies really points to is the general indecision of voters. As surveys around the popularity of Medicare for All, for example, have repeatedly shown, voters are responsive to both positive and negative messaging around policies, sometimes in ways that are contradictory. Rather than present a clean narrative of which policies are popular, and should therefore be adopted, the report’s authors have merely reinforced how fickle public opinion can be.

Trust Me, I’m a Democrat!

The authors assert that Democrats are less trusted on the issues voters care most about—and they take it for granted that this is because the party has moved left on these issues.

To drive home this message, the Deciding to Win authors present data that purports to show that Democrats are trusted less on issues that voters prioritize, whereas Republicans are trusted more in those categories. In one table, “drug abuse and addiction” ranks as the top issue that voters care about, although Democrats trail Republicans by just one percentage point—hardly dire. The next issue, “income inequality,” shows Democrats with a two-point lead. Meanwhile, “race relations” and “the environment,” dismissed elsewhere in the report as fringe concerns, poll at 38 and 37 percent importance, respectively, and are areas where Democrats enjoy five- and ten-point advantages.

Does this really paint a foreboding picture for Democrats on the ideological front? The argument is unconvincing. Of the top ten most important issues, Democrats are net positive on five, according to the report’s own data. And with only a fifteen-point spread between the most and least important issues, voters’ concerns are varied. There’s no single issue dragging the party down.

Progressives do agree with the report’s authors that the Democratic Party has trust issues; however, we have long argued that Democrats’ trust problem stems not from ideology but from hypocrisy. A Democratic senator will decry wealth inequality on the Senate floor, then attend a lavish fundraiser hosted by titans of capital that evening. That disconnect, paired with the consultant-approved language that defines mainstream Democratic messaging, does more to erode trust than any policy position.

Moderate For Whom?

Having dispensed with establishing which policies are popular and which are not, Deciding to Win’s authors devote much of the rest of the report to an inducement to moderation in Democratic candidates. They urge Democrats to “moderate” on cultural issues like gender and queer rights, but then later note that banning discrimination against LGBTQ Americans in housing and employment enjoys clear majority support.

This incoherence continues as the authors try to define what a “moderate” candidate is. A moderate is someone who simultaneously, somehow, is critical of the status quo but against radical change of any sort. They are at pains to note that “frustrations with the status quo are not the same as a desire for socialism,” making sure that the reader knows who the real enemy is—and it’s no coincidence that these are the same enemies MAGA Republicans describe. The report goes on to say that “large majorities of Americans continue to have positive views of capitalism…[and] negative views of socialism.” While the reports the authors cite do show an overall preference for capitalism among all Americans (roughly 57% approval versus 39% disapproval) they fail to note that among Democrats, there is actually a higher preference for socialism than for capitalism, per the same studies.

The studies the authors cite only go as far as 2022; more recent polling, conducted this year and by the same pollsters, show that just 42% of Democrats approve of capitalism, with 66% preferring socialism, the reverse of the trend the authors are trying to depict. While it’s not clear why the authors relied on older studies and didn’t update their report with newer polling, it’s obvious that more recent reporting significantly complicates the idea that socialism isn’t popular among Democratic voters.

Elsewhere, moderates are celebrated for their ability to overperform electorally while “extreme” candidates underperform. The authors point to candidates who beat the trendline swing from Democratic to Republican support in districts around the country, but don’t appear to be taking factors like incumbency, local conditions, or individual campaign contexts into account. This logic has long been echoed by pundits eager to reduce politics to electability charts. But all it really says is that maintaining the status quo is easier than changing it—an observation so banal it borders on platitude.

The real question is whether it’s worth pushing for change even if it’s harder. Joe Biden’s 2020 reassurance to wealthy donors that “nothing would fundamentally change” may have been politically clever on the heels of the first, chaotic Trump administration, but should that really be the bedrock of a party now hemorrhaging enthusiasm and credibility? Or, should the party push for progressive policy—much of which, even Welcome’s authors concede is “popular”— and try to win voters back with an ambitious vision for the future?

Joe Who?

Part nine of the report, “Lessons from the Biden Years,” briefly addresses what most party insiders now recognize as Biden’s catastrophic decision to run for reelection. The section also faults Democrats for failing to focus on inflation and “kitchen-table issues,” yet never mentions the administration’s enabling of Israel’s genocide in Gaza. In fact, the entire document refers to Israel and Palestine only once, in a footnote claiming foreign policy is not of significant voter interest. That would be news to the 101,623 Democrats who voted “uncommitted” in Michigan’s primary to protest Biden’s Gaza policy. Kamala Harris went on to lose Michigan by just over 80,000 votes.

The authors and Welcome backers also fail to acknowledge that they represent the exact political tendency that, in the run-up to the 2024 election, insisted that Biden was the only viable candidate to defeat Trump. While progressive organizations were sounding the alarm about Biden’s abysmal polling and the enthusiasm gap between the parties, corporatist “moderates” insisted that staying the course was the only reasonable way forward. After Biden dropped out, these same voices were those arguing against an open Democratic primary and enabling Harris’s hasty coronation as the party nominee. “Deciding to Win,” predictably, is devoid of any self-reflection or criticism of the role that the party’s conservative tendency played in this trainwreck.

While deriding Harris’s inability to break away from Biden’s lackluster economic policies, the authors invoke Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez as examples of effective economic messaging, citing their “Fighting Oligarchy” tour. They even concede that left-wing economic populism gets “some things right”—though, predictably, they never specify what it supposedly gets wrong. Instead, the report returns to its old refrain—that unpopular positions are unpopular—circling endlessly back to itself.

A Different Way Forward

What Deciding to Win and similar analyses miss is that the Democratic Party’s core challenge isn’t that it has moved too far left, but that it doesn’t seem to know what it stands for. The party is collapsing under the weight of its endless focus-grouping and message-testing without an ideological core to orbit around. Progressives and moderates alike agree that Democrats have lost ground with non–college-educated voters. But this erosion isn’t the fault of progressives pushing economic populism; it’s the result of the moderate wing’s long-standing bet that such voters could be replaced by suburban professionals—an experiment whose results are now in.

In the end, Deciding to Win reads less like analysis and more like self-justification for a faction of donors and consultants eager to blame the left for their own failures. The report’s core message—that moderation is always safer, that populism is suspect, that electoral success can be engineered through triangulation—may comfort those who fund it. But it offers little insight into the actual dynamics reshaping American politics.

The real question is whether Democrats want to be the party of careful calibration or of conviction. If the former, they may continue winning the occasional race while losing the broader argument. If the latter, they’ll need to stop listening to reports like Deciding to Win and start deciding what they actually believe.

Recent Posts

A War With Iran Would Not Be a One-Off Event But a Disastrous Ongoing Rupture

February 26, 2026

Take Action Now If Congress cedes its power to stop a war with Iran, it will fully erode any lingering promise of democratic restraint.By Hanieh…

New Addition to List of Nuclear Near Catastrophes

February 25, 2026

Take Action Now Debris flew for great distances — many times the distance of 270 meters to a nuclear reactor and nuclear storage facility.By David…

Gavin Newsom’s last budget belies his ‘California for All’ pledge

February 24, 2026

Take Action Now Yet, even as the state is poised to lose billions in federal funding, and millions of Californians are losing access to health care…

Israel and American Hawks are Pushing U.S. to Iran War With Catastrophic Consequences

February 23, 2026

Take Action Now At the World Health Assembly in May, member states may endorse an unprecedented strategy declaring that health is not a cost – but…