By Micah L. Sifry, TheConnector

Last night, my hometown of Hastings-on-Hudson, NY, held an online town forum on cannabis. New York State recently passed the Marijuana Regulation and Tax Act, legalizing the adult-use market for weed. Under one of its provisions, all the towns in the state have until December 31st to decide whether to opt in to allow cannabis dispensaries and on-site consumption lounges to apply for licenses to operate, or to opt-out. I tuned in for an hour to listen. Perhaps one-third of the residents who spoke were in favor of opting in, while the remainder either were passionately opposed or wanted to wait and see. (If a town opts out now, it can opt in at some later date.)

For the most part, the online forum was civil, though one speaker accused a town resident who is a lawyer specializing in the nascent cannabis industry, who the town trustees had earlier tapped for advice, of being no better than a tobacco industry lawyer. The people in favor of opting in had lots of evidence supporting their position: Cannabis has therapeutic value; making weed legal for adults doesn’t increase its use among minors; retail sales of cannabis doesn’t lead to increased crime rates or drops in property values. And, to help right the historical wrongs intensified by the War on Drugs, half the dispensary licenses that will be issued in New York State are being reserved for people of color and other communities disproportionately hurt by that war, and women.

The opponents had their own studies to cite, and unlike proponents, they are organized as a civic group called Hastings Opt Out. A model letter to the town trustees that they’ve written argues that the rates of pot and alcohol use in our town are much higher than the national average, and claims that proximity to dispensaries would lead to more use. That in turn, they say, will lead to increased levels of depression, psychosis, suicidal ideation, lower cognitive functioning and lack of motivation. They also argue that since the law is so new, we don’t know enough about how pot sales in the state would be regulated. The letter warns, darkly, that however that plays out, such regulation would “not be within local control.” [Emphasis in the original.] Adding dispensaries to our town, they write, “is not social justice…it is commercialization” and it will “permanently change[] the nature of our Village downtown.” Somewhat apocalyptic language for such a small issue, if you ask me.

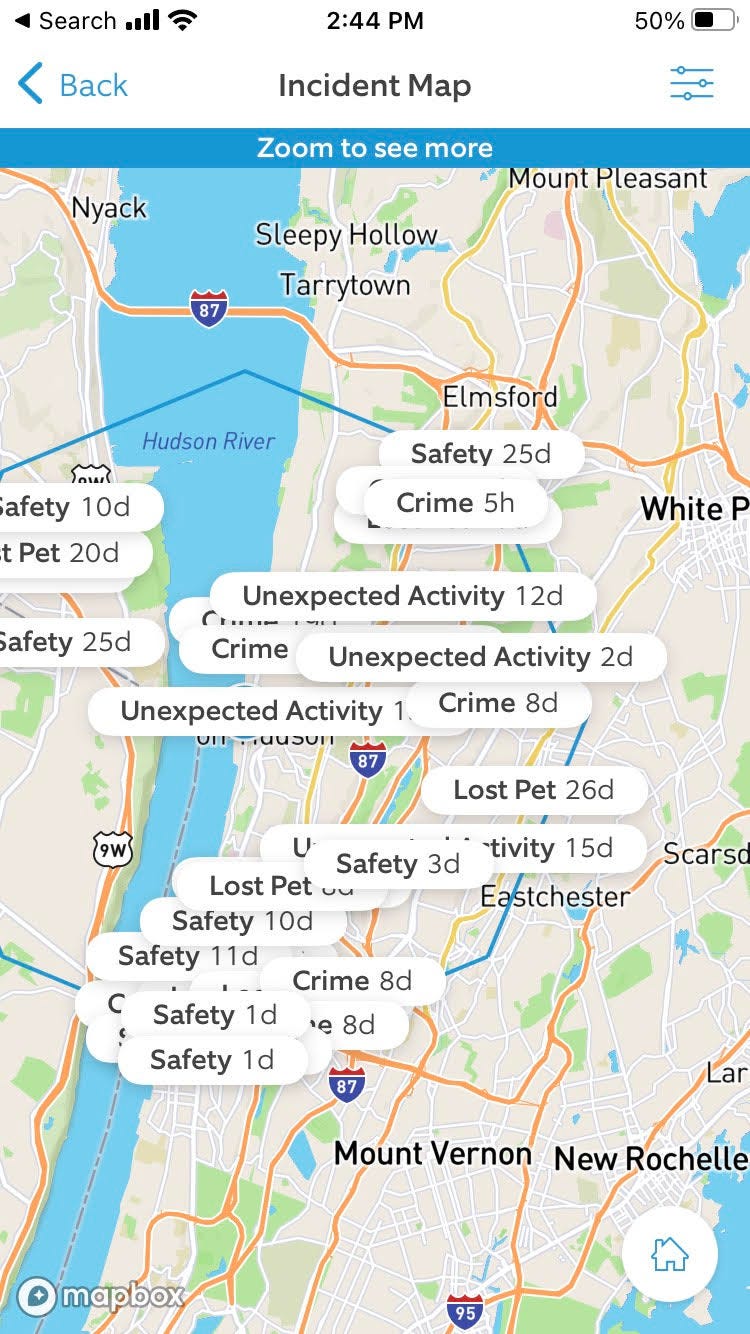

What is particularly telling to me about the local revolt against legal cannabis is what people here aren’t upset about. In just the last few years, a very greedy corporation has penetrated our town, selling a product that makes people more anxious and fearful. No exact numbers on its use are available, but I’m willing to bet that at least a quarter of my neighbors are hooked on it. I’m talking about Amazon’s Ring video doorbell and its Orwellian-named Neighbors app, which drives attention to local incidents of petty crime and “unexpected activity” (see image below). Because it comes from Amazon, we have no local control over the weaponization of the information Ring/Neighbors produces, and its spread is absolutely changing the nature of neighborhoods. But its prevalence is not an issue, even though we have lots of evidence that these home surveillance networks reinforce white fears and prejudice against people of color and the poor.

Now, a little context. Hastings-on-Hudson is a town of about 8,500 people. In 2020, Westchester County voted 67-31% for Joe Biden; here in Hastings the least blue precinct voted 70-29% for him. Most of the other precincts in town were in the 80 to 90% range for Biden. The town is mostly white and affluent; three-quarters have a college degree and many work in the creative arts. Just one percent are below the poverty level. The crime rate is almost non-existent. You might think that all these conditions would lead to more openness to change, but even in this very secure little village just north of New York City, people want the status quo.

Is this just NIMBYism? I don’t think so. In 1955, when William F. Buckley launched the conservative magazine National Review, he decried the “radical social experimentation” being embraced by “literate America” that had overrun elite campuses and was now “running things.” He claimed that the federal government, which was then just inching towards dismantling formal race segregation, was imposing a new utopian social order and exceeding its sole mandate to protect life, liberty and property. His new magazine, he wrote, “…stands athwart history, yelling Stop, at a time when no one is inclined to do so.”

I do not think the liberals of my town are anything like the conservatives that clustered around Buckley’s flag. But I think the underlying impulse, to yell Stop, to slow down needed change, is the same, and those of us who want more change need to listen carefully. Years ago, when I was reporting on Ross Perot’s third-party movement, I spent some time in the Twin Cities area, trying to understand how Jesse Ventura, a professional wrestler-turned-talk radio host, had managed to win an upset victory in a three-way race for governor against two conventional major party candidates. I was particularly curious how he had gotten more than 50% of the vote in the counties north and west of the Twin Cities, especially vote-rich Anoka County. Part of the answer was cultural. People in that county were somewhat more working class, more inclined to drink beer than wine, local politicos told me. Ventura had racked up votes barnstorming the area’s big sports bars the weekend before the election. He just connected with them at a visceral level.

But political demographer Myron Orfield, who teaches at the University of Minnesota, had an additional explanation. When the rate of growth in a county gets too fast, he told me, more people start voting no. Something about the speed of destabilization that comes with rapid population growth—the increased traffic, the new faces on the street, the expanded demand on local schools—all of that together tends to boil over in opposition to more change. And one place where people often vent that anxiety most easily is local politics like school board elections, or town budget votes. Usually, the out-party batters the in-party; Ventura’s victory was a rare example where a viable third-party candidate, helped by the state’s relatively generous campaign finance laws, media that included him in major TV debates, and same-day voter registration, could turn that desire to vote against both in-parties into a win.

Now, we’re not in a period of rapid population growth in my little town. School enrollment is up somewhat, but that’s not what is making people anxious. Despite, or perhaps because of, the security of this suburban bubble, people seem much more unsettled about the present and the future. Things haven’t “returned to normal” by any measure: this morning I drove past the big commuter parking lot next to the Metro-North train station by the Hudson River and after years of it being impossible to find a spot there, it was only half full. This isn’t a “new normal,” either.

We live in a time of rapid and discontinuous change, but none of our “authoritative” institutions are designed to help us thrive during such periods. Families, schools, religious institutions, businesses, and government are all built around an assumption that tomorrow will be more or less like today. It’s a very shaky assumption. Since 2000, we have experienced at least nine cataclysmic events, or near-catastrophes: the Bush-Gore election standoff, the 9-11 attacks, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, the 2008 global financial meltdown, the 2011 debt-ceiling crisis of 2011 when the US almost defaulted, the 2016 Trump election, the Covid-19 pandemic, the 2020 George Floyd uprising, and the January 6th insurrection. At an only slightly less jarring scale are the wave of gigantic climate events that have hit the US in recent years, from various hurricanes devastating Houston, New Orleans and Puerto Rico to the massive fires out West and the heat wave in the northwest and the Texas cold snap of last spring.

The Internet has sped up both the pace of change and our perception of that pace. It’s become easier to build in-groups around a commonly shared belief, making mass protest movements like the Women’s March and the Black Lives Matter scale much more quickly. The same is true for the #MakeAmericaGreatAgain mob and today’s backlash against public schools for trying to educate kids in more inclusive ways. And not only do movements grow faster, small grievances and outrages get amplified far more quickly. In-groups also get stronger in part by targeting outsiders, and we most definitely should credit Facebook and the other major social media platforms for making life meaner since they became ubiquitous.

It is both true that change is coming at us faster, and it feels more true even when our own bucolic bubble may be insulated from the biggest shock waves. This is why I’m a broken record on the need to add more friction to digital life and to foster more local community spaces where diverse individuals can discover what they may have in common and learn how to navigate difference more fluidly. When people are fearful, they gravitate towards strongmen to protect them. Those of us who want to foster more change need to figure out how to defuse that tendency, not feed it. If a safe suburb like mine can’t take a chance on the more compassionate, less punitive version of the future represented by legal, adult consumption of cannabis, imagine how much more the resistance to change from people in less prosperous communities who imagine that teaching their kids about America’s full history will damage their self-esteem. If we’re going to make it through the 2020s successfully—a truly big “if”—it will only be by strengthening our ability to listen to each other and build trust that can reduce fear.

Recent Posts

Coalition of Antiwar Groups Launches National Campaign Calling for Jeffries and Schumer to Step Aside from Leadership

March 11, 2026

Take Action Now “Schumer and Jeffries have failed their party and country through wobbly leadership when firmness and clarity are needed in opposing…

The Bases Basis for the Iran War

March 11, 2026

Take Action Now The economic impact of this war — through oil, tourism, and otherwise — is likely to continue to rub Gulf nations’ faces in the…

Israel’s Greatest Weapon Was Fear — And It Is Now Failing

March 10, 2026

Take Action Now Israel’s war on Iran reveals a deeper crisis: the collapse of a psychological doctrine built on fear and invincibility.By Ramzy…

When Millions Marched for Immigrant Rights

March 10, 2026

Take Action Now The 2006 mega-marches against legislation to criminalize the undocumented revealed the hidden power of immigrant workers.By Alan…